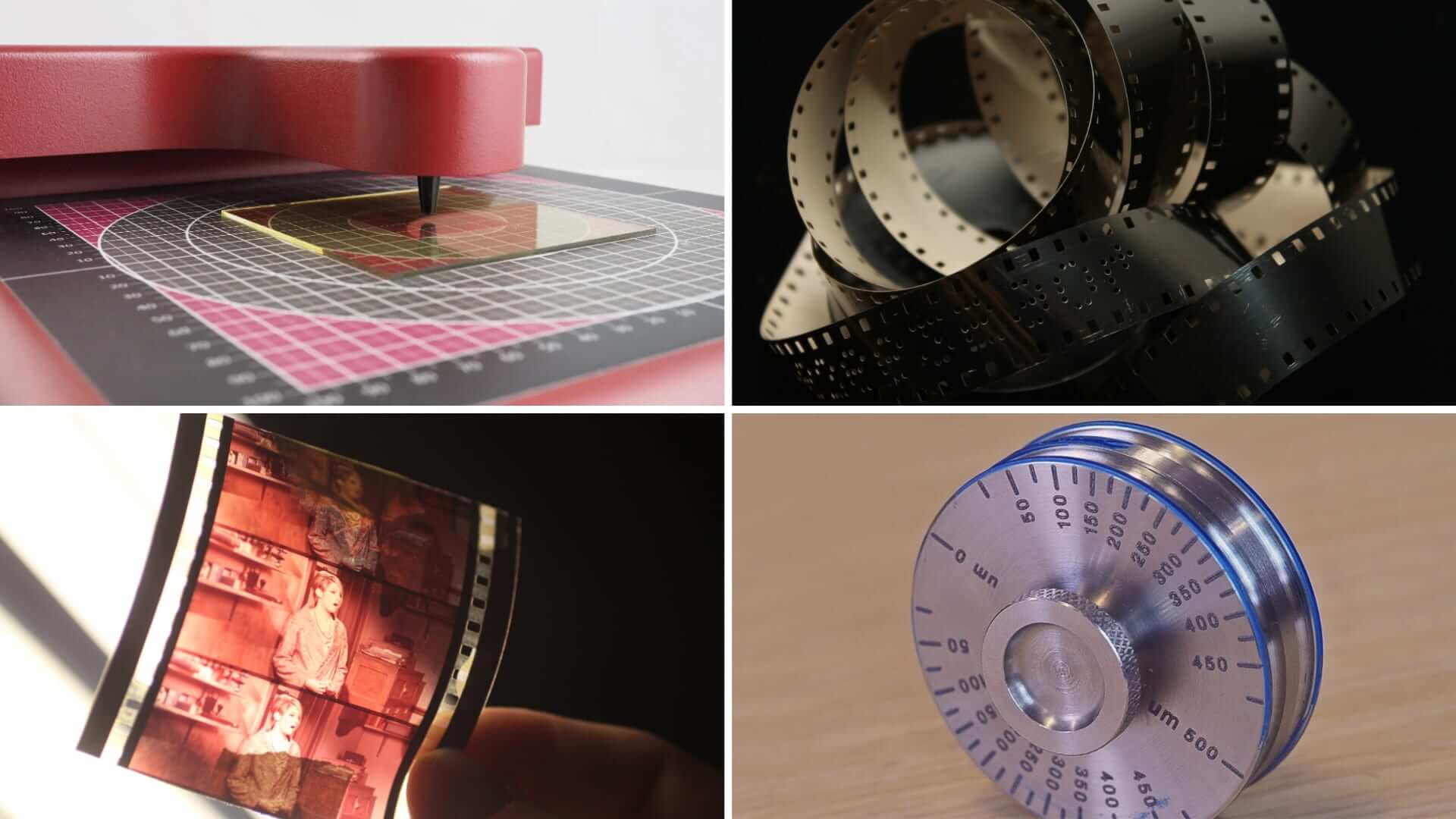

When shooting a motion picture on physical celluloid, there are different types you can choose from. Each type will be a certain width, which contributes to its quality, size, grain count, and more. When identifying the different types of celluloid used in filmmaking, we refer to these strips by their film gauge, which is often, but not always, recognized by how many perforations it has. But what is film gauge, why does it matter, how else can it be identified, and which one should you choose?

Film Gauge Definition

Film gauge explained

There are a variety of film gauges that have existed since the beginning of photography and filmmaking. But before we dig too deep into the most popular and used formats, let us first provide a film gauge definition that works for all gauge types.

FILM GAUGE DEFINITION

What is Film Gauge?

Film gauge is the literal width of a film strip, as measured in millimeters. This width can determine the quality of the film itself, how much light passes through it (during filming and projection), and the literal size of the film strip. All types of film gauges bring with them unique advantages and disadvantages. All of which contribute to the overall look and feel of any given production.

Film gauge characteristics:

- Perforations on the sides of the film strip, which make it easier to identify what sort of film gauge it is

- The bigger the film gauge number, the wider the literal strip of film

- Larger gauges producing better quality images vs lower gauges producing lower quality imagery

Before we go any further into the weeds of this subject, let us provide you with a comprehensive and helpful video courtesy of Fandor. The video below covers the generals of film gauges and why they matter for a film’s look and mood.

Gauge film • Fandor breaks it down

Just so you know, there have been a variety of film gauges in photography, but we don’t want to make your head spin, which is why we will be covering the most popular and well-known film gauges still in use today.

Home Gauge Movies

8mm

Originally produced during the Great Depression of the Pre-Code 1930s, 8mm film was created for amateur filmmakers to easily pick up and use. It features one perforation per frame, and can even use just one on the left as opposed to having one on each side.

As a lower quality film gauge, it tends to produce a very soft image. This also appears very grainy and maybe even dirty. In general, 8mm filmmaking was meant for filming your family during a cookout more than a lavish full production. But that’s also why it was marketed to amateurs: it was cheaper than the higher quality 16mm format (which we’ll get to soon).

Analog Resurgence does a great job covering standard 8mm film gauges, which can be seen in the video below.

Gauge film • Covering 8mm

There have been a few variations on 8mm film, but the most popular and well known is Super 8. Created in the mid-1960s, it uses more of the exposed area on the strip, meaning greater quality of film.

Probably the most important feature of Super 8 is that it provided its film in a cartridge, which used a loading system. So, not only was Super 8 a better way to shoot in 8mm, but inserting and replacing the film itself was also tremendously easier.

Indie Film Gauge

16mm

Before (and even after) 8mm, there was 16mm, which has two perforations on each side of the frame. While also targeted towards amateur filmmakers in the 1920s, it was used for lower-budget productions, ranging from educational films, commercials, and television programs.

As a result, it became fairly well known and used among amateurs, especially since it could provide color images. This also fueled its usage for serious productions on TV, getting a lot of use out of British stations and various industries.

Like 8mm, 16mm had a popular variation in Super 16; it takes up more of that exposed area to produce a better quality image. While standard 16mm has a native aspect ratio of 1.37:1, Super 16 managed to go widescreen with 1.66:1 (which can be easily cropped to 1.85:1).

The Royal Ocean Film Society has a humorous but informative video that explains the appeal of 16mm, while also talking about why it’s still used and what effect that has on the film and its audience.

Gauge film • 16mm film gauge

Due to its special look and feel, on top of being cheaper than 35mm, 16mm film gauges have stayed popular with different types of filmmakers. And unlike 8mm, there are very notable films that have been shot on standard and/or Super 16mm, with some filmmakers actually choosing it as a primary format.

In the video below, writer/director David Lowery explains in brief detail why he decided to use Super 16 for his film The Old Man and the Gun (2018), which gives off a dirty but warm feel reminiscent of how films looked in the time period the film is set in.

Gauge film • David Lowery on using Super 16

Darren Aronofsky has used this film gauge a lot, which adds to his distinctive directing style. These 16mm shot films includ his first, Pi (1998), as well The Wrestler (2008), Black Swan (2010), and mother! (2017).

Wes Anderson also used Super 16 for his film Moonrise Kingdom (2012), which gave the period piece a distinctive look unique in Anderson’s filmography. The film was also shot in 1.85:1, a ratio Anderson is not very known for. More recently, Jonah Hill’s directorial debut, Mid90s (2018), was shot on standard 16mm and presented in 1.33:1.

Related Posts

Standard Film Gauge

35mm

It does not get more traditional than 35mm, easily identified by four perforations on each side of the frame. It has remained the standard since movies were first invented in the 1890s. The majority of movies that were shot in the 20th century were done on 35mm film stock, which also resulted in variations and innovations during that century.

35mm helped standardize the Academy ratio, which made sure all major motion pictures were in the 1.37:1 aspect ratio (which is the native ratio of standard 35mm film gauges for making movies).

Even when 20th Century Fox licensed the use of the anamorphic widescreen technique to create CinemaScope, 35mm film was still being used in a creative way. Panavision would later eclipse CinemaScope, being the primary and favorite of filmmakers for decades for filmmaking with anamorphic lenses.

Gauge movies • How 35mm influenced cinema

The widescreen revolution of the 1950s resulted in many studios cropping standard 35mm film from 1.37 to 1.66:1, 1.85, or 2:1. This style of having a native 1.37 ratio and cropping, either during or in post-production, is still in use today, extending to the new world of digital.

VistaVision from Paramount Pictures found a new way to use 35mm: horizontally. Film is typically shot and projected vertically, but VistaVision went horizontal in order to use more space on the film strip, which resulted in higher quality imagery and double the perforations (on each side).

As cool as it was, VistaVision was not meant to last, as Paramount abandoned it after a few years. Check out this video on the restoration of Richard III, shot in VistaVision and directed by its star, Laurence Olivier.

Gauge film • Richard III was shot in VistaVision

Some interesting techniques with 35mm kept happening, like Techniscope, which used two perforations in order to shoot films with a wider 2.39:1 ratio without anamorphic lenses (at the risk of extremely grainy footage).

However, the dream of ‘Scope-without-anamorphic' came with Super 35, a process which, like Super 16 and 8 before it, simply used more of the space in a film gauge. Taking all that native space available, films shot in Super 35 were often aiming for a 2.39:1 aspect ratio, but you can also use it for films in 1.85:1. In most cases, Super 35 gives your framing three perforations as opposed to the full four, most prominently for 2.39 films.

Related Posts

Large Film Gauge

65mm/70mm

While most film studios in the 1950s and ‘60s were making things happen with 35mm, a few select companies were working with 65mm, better known as 70mm. A format twice as large as 35mm, the amount of perforations are usually five per frame side.

Often using a standard aspect ratio of 2.2:1, companies like Todd-AO were at the forefront of this very special film gauge, which intentionally emphasized spectacle. This meant that films shot and projected in this film gauge were meant to be shown at limited engagements, as well as show off the tech used to film the movie. There was also Ultra Panavision 70, which extended that ratio to 2.76:1, but not too many movies used either of these processes.

Gauge movies • 70mm’s history and importance

While traditional 70mm film gauges are still used, these days the most common type of 65mm filmmaking comes from IMAX. Taking a cue from VistaVision, IMAX movies are shot horizontally with fifteen(!) perforations on the top and bottom of the film strip. Needless to say, there are no bigger film gauges than IMAX, which is why the clarity and sound of IMAX pictures are second to none.

Since the 2000s, many big time filmmakers have dabbled with IMAX. Some going as far as to film a large chunk of their movies with these cameras, lenses, and film stock. Christopher Nolan is easily the patron saint of IMAX (and physical film). Almost all of his films from the last ten years have used IMAX photography extensively. The use of such large film stock to aid in spectacle has helped Nolan’s directing style stand out in contemporary cinema.

UP NEXT

Why aspect ratio matters

Now that you know about the most prominent film gauges in filmmaking, it might do you some good to learn more about aspect ratios. We cover the most basic ratios you’re bound to see and use, along with how they are used and what effect they give off in the films they appear in.

Up Next: Aspect ratio explained →

Showcase your vision with elegant shot lists and storyboards.

Create robust and customizable shot lists. Upload images to make storyboards and slideshows.