Exposition in film or screenwriting is one of the most difficult aspects to master. It’s necessary for our audience to understand our characters and plot, but we don’t really want the audience to be aware of exposition, in and of itself.

When that happens, it can jar the audience right out of our story. And it also just makes our writing look bad. In this post, we’ll take a look at ways to avoid the common pitfalls of clunky exposition, as well as some excellent examples of exposition that have been seamlessly integrated into the overall narrative.

Exposition is simply information for the audience’s benefit. It can be background information about a character that helps the audience better understand her motives, or the choices she makes in the narrative.

Exposition Definition

What is exposition?

Exposition is a comprehensive description or explanation to get across an idea. Exposition is a device used in television, films, poetry, literature, music, and plays. It is the writer’s way to give background information to the audience about the characters and setting of the story.

Exposition can be dialogue, narration, or even visual information the audience receives that helps them better understand what is going on in the story.

What can exposition do?

- Reveal more about character

- Describe the story world

- Reveal theme

Writing exposition can be historical or contextual information about our story’s setting, or even the rules that govern our world. We often see this kind of exposition in the form of a prologue.

Prologue Definition

What is a Prologue?

A prologue is an introduction, separate from the rest of the story. It provides a history, or gives important details about, the setting and/or characters up to the point where the story begins.

As a screenwriter, you’ll have to be able to provide these crucial tidbits of information in a way that doesn’t bring the story to a grinding halt or overwhelm the audience.

So now that we have that taken care of, let’s take a look at some ways we can weave exposition into the narrative.

TIPS FOR BETTER EXPOSITION

1. Exposition should be brief

First things first. Brevity is key. No matter how you choose to deliver your exposition, always keep the audience’s patience in mind.

This is mostly relevant when you’re using dialogue to give expo. (Although, we wouldn’t want a 10 minute montage either).

We don’t need to overdue the point. If we’re revealing exposition in an organic way, using character, genre, or even conflict to do it, we probably won’t run into this problem. Let’s dive a little deeper into this.

Revealing Exposition

2. Exposition through dialogue

In screenwriting, there are several conventions for conveying information to the audience. Some are specific to certain genres, or characters, and audiences readily accept, even expect them.

But convention can quickly turn cliché. Our screenwriting goal is to avoid cliché by bringing something new and interesting to even the most basic story.

The easiest way to exposit information is by having characters talk about it. Dialogue can be a natural way for your characters - and the audience - to learn things they need to know about the overall narrative. But the dialogue has to be motivated by something. Otherwise it may appear to be too “on the nose.”

There are ways of including necessary information in your dialogue that are realistic for the context.

This is true especially for certain genres. Let’s explore below.

Exposition in Film Methods

3. Exposition tropes of genres

Common tropes follow certain genres. For example, in the Fantasy genre scripts, there is often some kind of battle that has taken place, must take place, or inevitably will take place.

And if there is a battle, there is usually the big battle plan meeting. The leaders of the disparate allies discuss how they hope to vanquish the evil bad guys once and for all. Here’s just one example:

Exposition Examples: GoT Battle Plan

No doubt you have watched many versions of this same scene. While it’s pretty cliché in terms of how often you’ve seen it, these scenes are as organic as they come...in fact, it wouldn’t be believable if they didn’t have this scene. And what works is that we’re given important information about the coming battle - which ratchets up the suspense when the outlined plans inevitably don’t work.

Though audiences of Fantasy expect a scene just like the one above, as screenwriters it is our job to give those scenes an original spin.

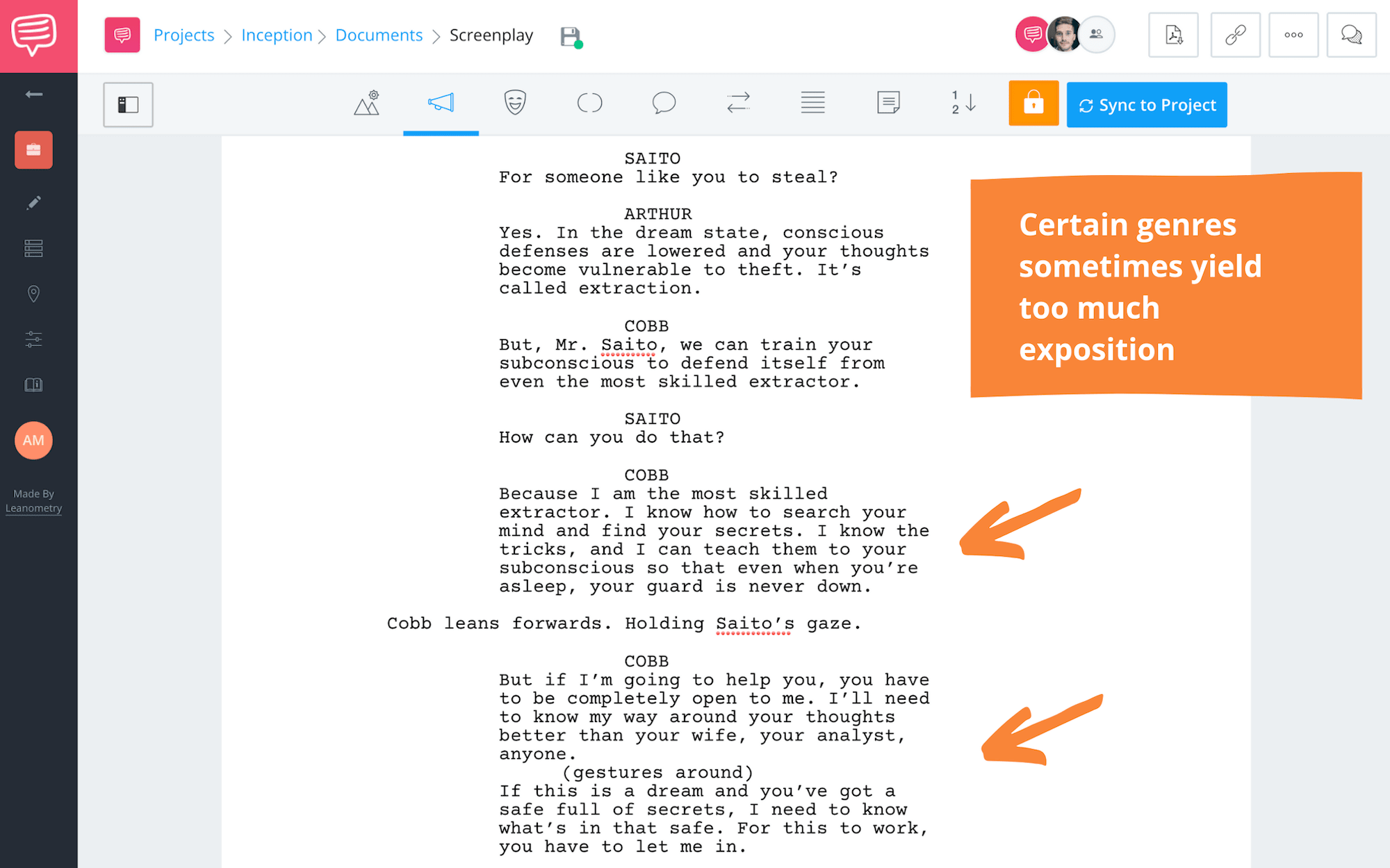

But this can be especially challenging with genres like Fantasy and Sci-Fi, where screenwriters are often tempted to write more exposition through dialogue than is necessary. There is a need to overly explain because the plot might be complicated. While Inception delivers, especially on Nolan's shot choice, there is a bit of over-explaining:

Exposition Examples: Inception Cobb Explains

We want to avoid clichés like having one character who explains everything, especially while it’s happening. Once you start writing, you'll be able to tell right away. You can use StudioBinder's free screenwriting software to practice:

Try to trust that your audience will be able to figure out most things without having it spelled out for them.

However, this leads into the next point, that there are certain characters who are organically built to reveal exposition. It’s literally woven into their character...

Related Posts

Exposition in Characters

4. Exposition through character

Choose characters whose job requires giving exposition.

For instance, teachers, doctors, or as we saw above, leaders of armies, are all great vehicles for delivering exposition. The amount of exposition they give agrees with the role they inhabit.

Why does this matter? Well, it's helpful when you're trying to pull off hard asks.

For example, trying to set up an important question or theme at the start of a film is a major responsibility. If a character's role is organic to the exposition they are giving, revealing major information is easy.

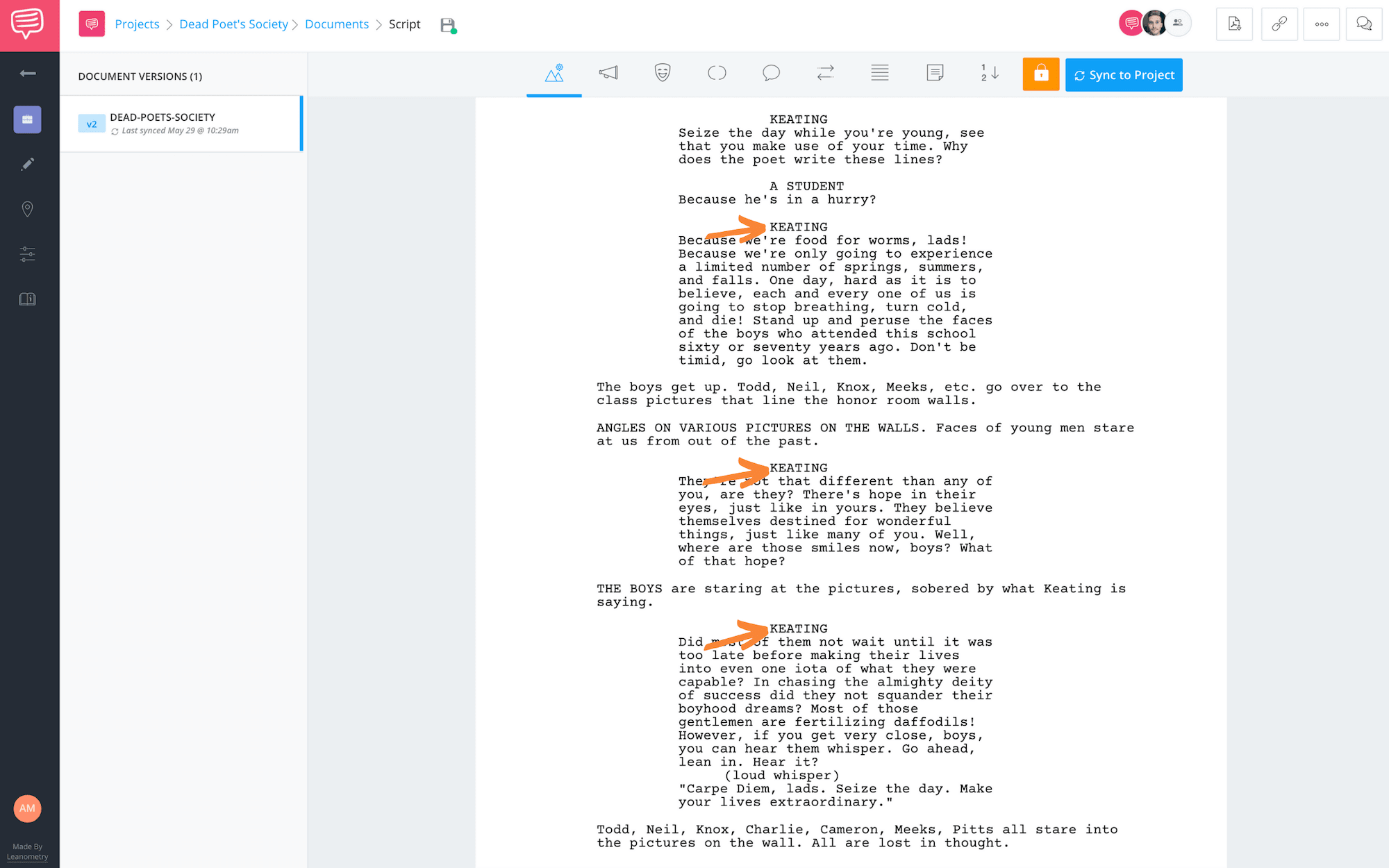

Let’s look at an example from Dead Poet’s Society that does this well. If you haven’t seen it, watch this scene below:

Exposition Examples: Seize the Day Lecture

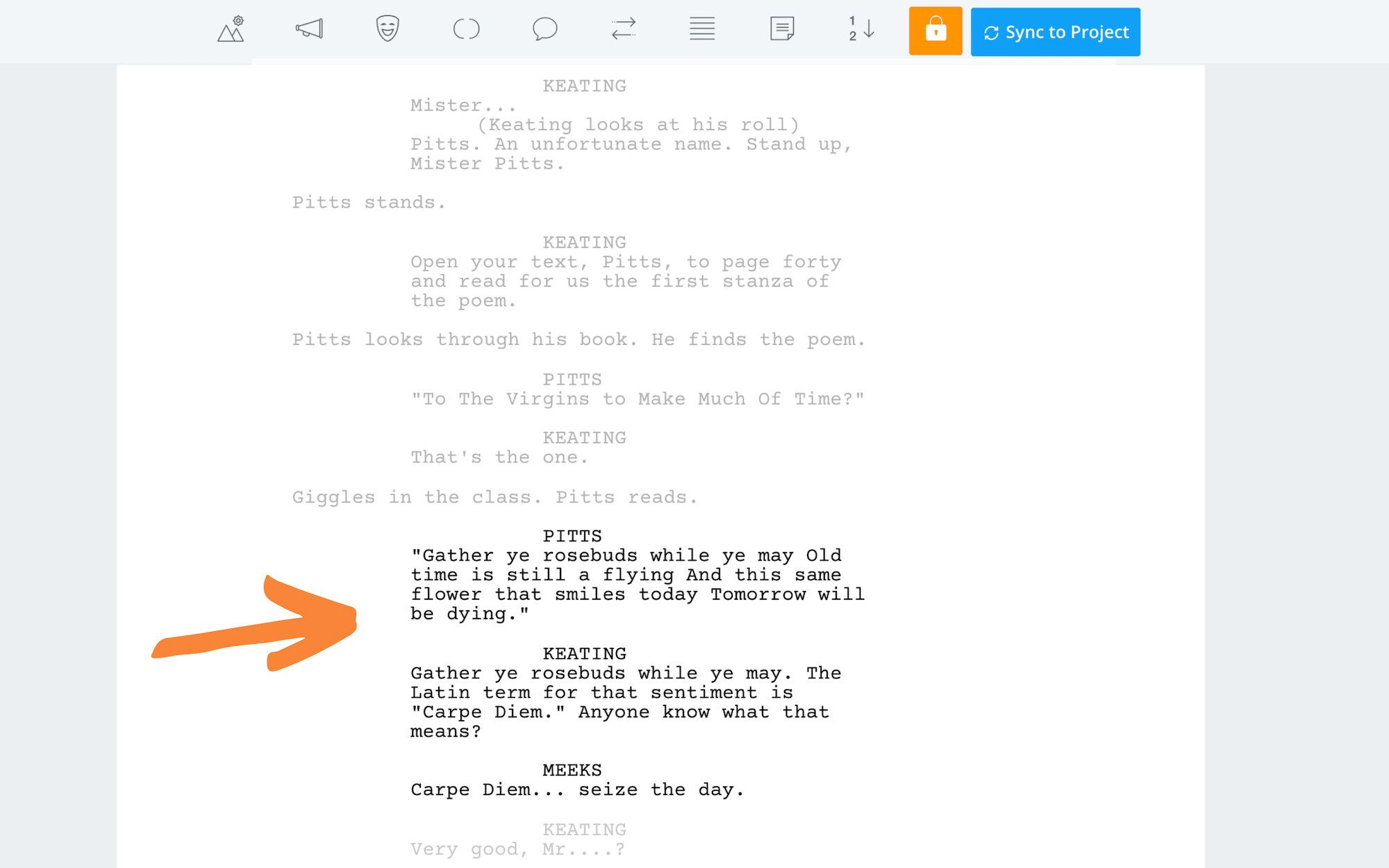

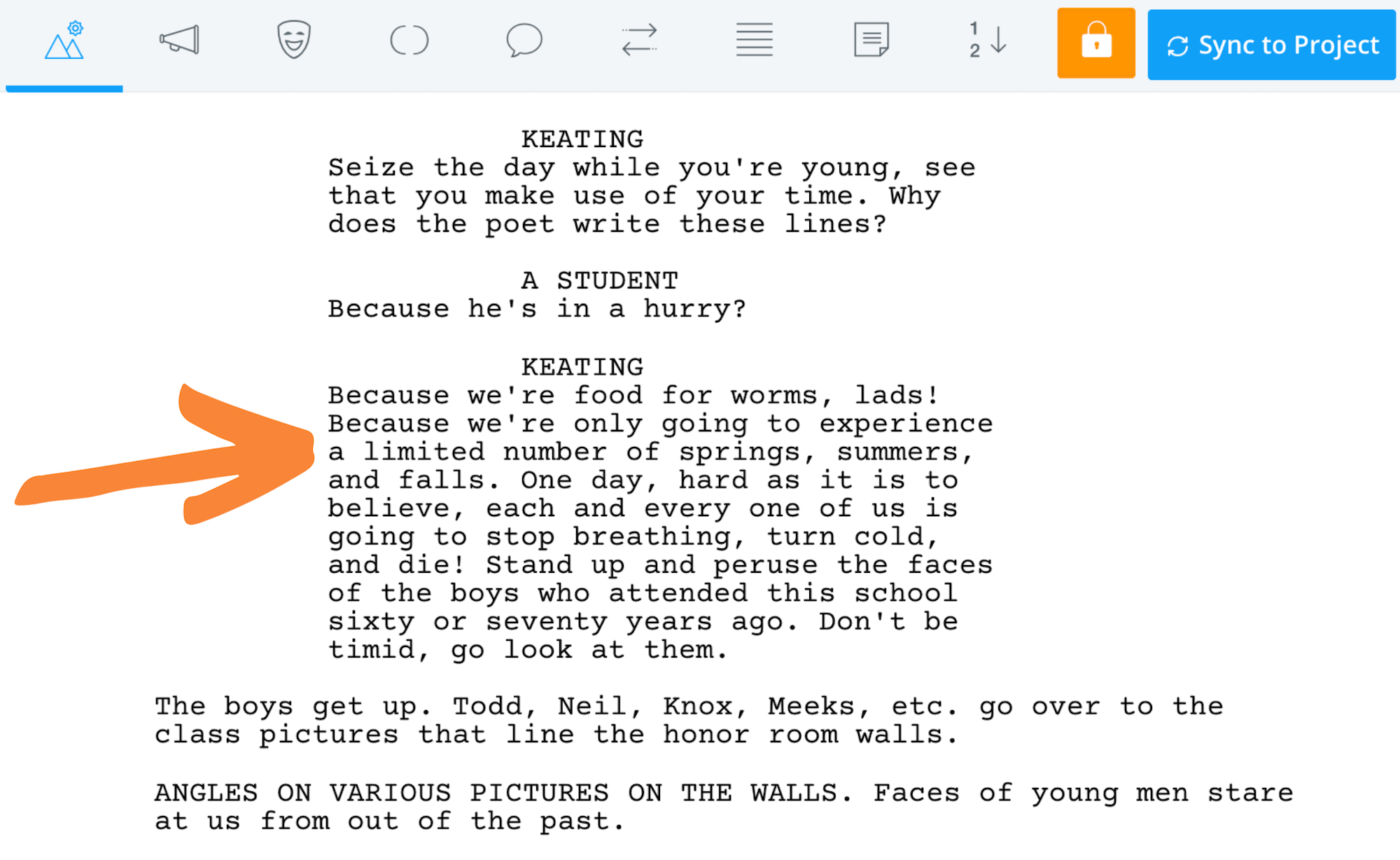

When we take a look at the scene scripted, initially, it looks like way too much exposition. There is a ton of dialogue. And it’s coming, mostly, from one person, Mr. Keating:

This is normally is a huge no-no. But why does it work here?

The character of Mr. Keating, his role as a teacher, is an organic way to reveal information to the audience because all he has to do is reveal information to his students. So even if the dialogue is lengthy, it's natural because that's how teachers normally act, that's how classes are.

But let's get more specific into the content of his lecture. And see how the specific information given was also just as natural.

Early on in the scene, Keating acknowledges that he too attended the strict prep school. We understand that he knows what it's like to grow up in Welton, and serves as motivation for his unconventional lecture about to come.

As he takes his students out of the classroom and into the hallway, he asks several boys to read a few lines from a Walt Whitman book. He calls out something critical in the poem, but also for the theme.

He calls attention to the theme of Whitman’s piece---“carpe diem” or “seize the day.” The confines of a prep school don't escape him, and he stresses the importance of this.

He has them look at pictures of deceased Welton students that hang on the walls in the hallway.

He continues giving this unique mini lecture comparing the current students to the deceased students.

"One day, hard as it is to believe, each and every one of us is going to stop breathing, turn cold, and die!"

While intimidating to some of the boys, Keating is a breath of fresh air. He provides some relief in the uptight school setting. And his lecture serves as a warning.

Mr. Keating’s unique style and nature are in perfect juxtaposition to the rest of the story world. He represents freedom, and choice, in a place that feeds off of conformity.

The iconic “seize the day,” lecture sets up the question:

Will the boys take control of their lives, and truly live? Or will they conform to their surroundings?

The rest of the film is watching how the boys take this advice.

Using character is an organic way to set up your story’s theme. Check out StudioBInder's entirely free masterclass on character development.

Related Posts

Exposition in Screenwriting

5. Exposition through conflict

Writing compelling conflict is a challenge all its own. But when you begin to get comfortable with the process, it’s one of the best ways to reveal exposition.

Again though, it needs to be organic.

We can’t have a character come up to another one and simply start yelling at them, revealing exposition that we don’t care about.

If we setup a reason to care about this situation, have some real stakes for the character if they fail at their goal, conflict comes easy. And when conflict starts showing, exposition starts flowing. (Sorry, it just felt right).

Now how does this work?

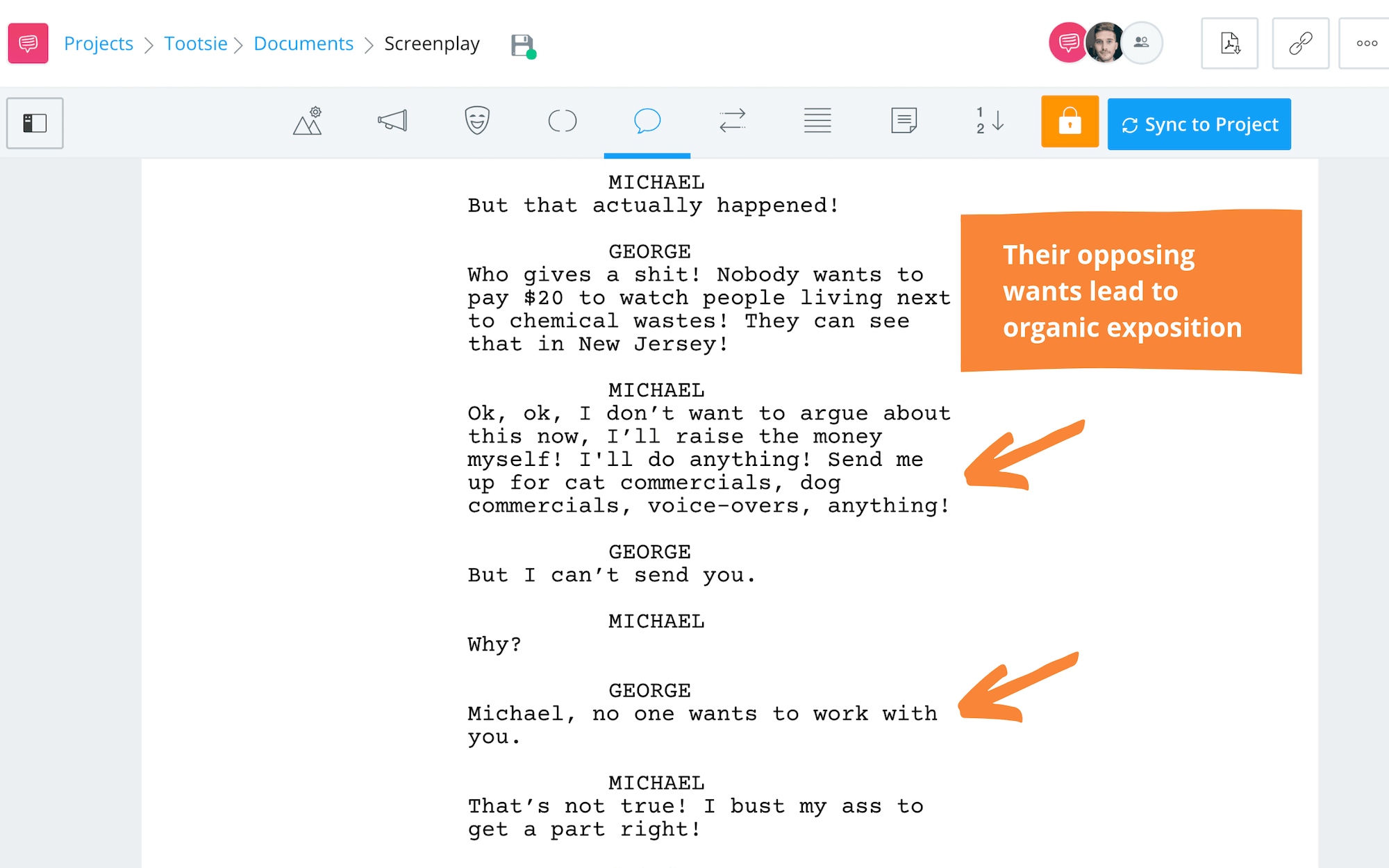

A great example of revealing exposition through conflict is in an early scene of Tootsie. Dustin Hoffman’s character is a bit of an arrogant guy, trying to become an actor in New York City. He feels pushed aside by his agent, and we see them arguing. Watch below:

Notice how every time Michael (Dustin Hoffman) says something, more information is revealed to us through the agent. Michael begs for work. He says he doesn’t care what the job is, "cat commercial, dog commercials," he just wants to be put up for something. But George refuses to put himself out there for this unprofessional client.

What Michael wants is in direct opposition to what his agent wants. We get exposition, a ton of it, but it’s motivated by this conflict:

We can see more information being revealed as the conflict mounts.

And with each ask from Michael, we learn more and more. The agent holds his position and begins to bring up issues from the past. Notice how the exposition flows in the conflict.

Everything in this scene is information that the audience needs to know about the character and the plight he’s in, and why he’s in it. It also helps setup the entire premise of the movie - he needs to become a different person (a woman) to get more roles.

Of course, there are a ton of other ways to reveal exposition without using dialogue. Let’s explore the idea of “showing, not telling,” as it relates to exposition.

Related Posts

Show, Don't Always Tell

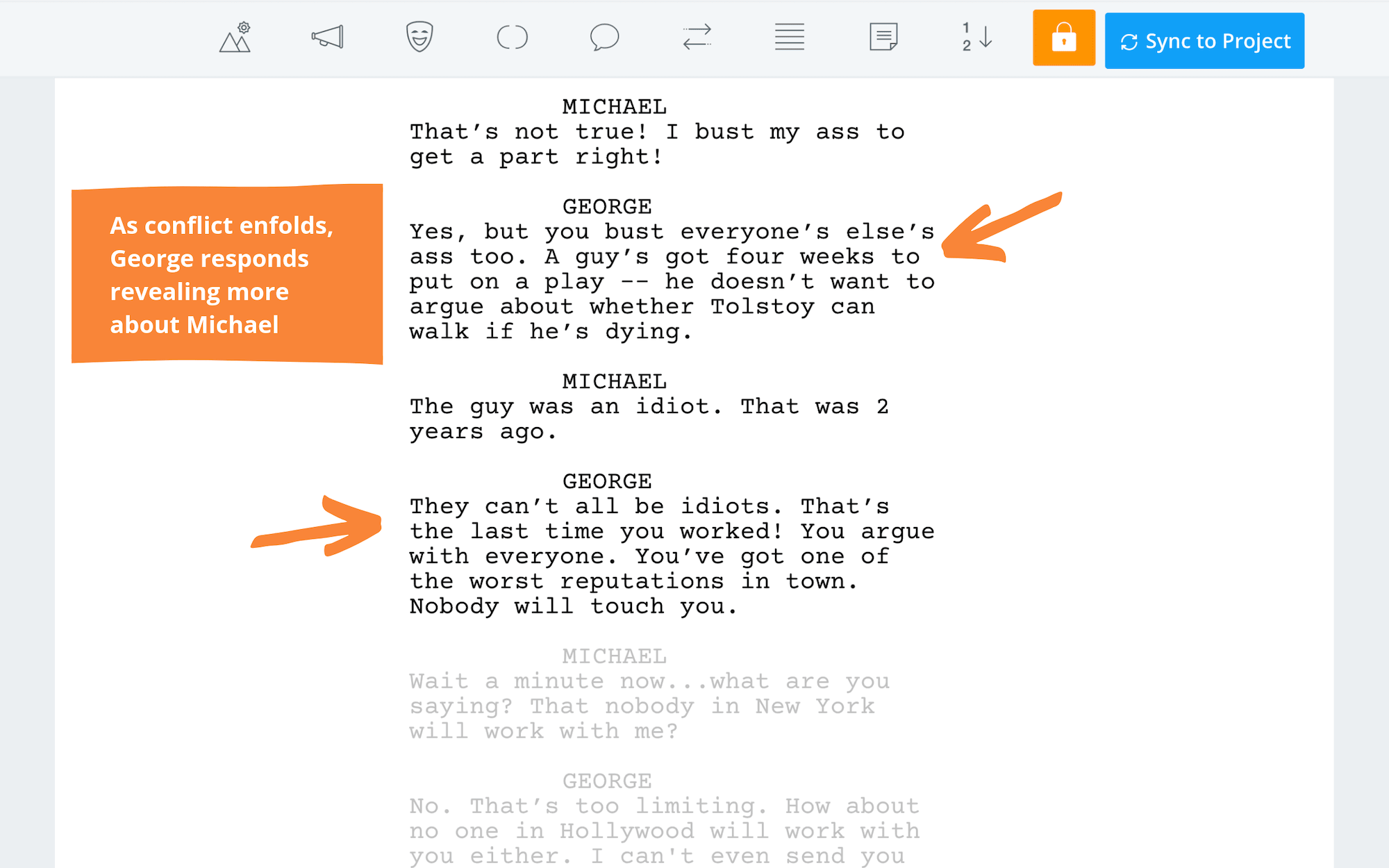

6. Exposition through montage

Writing for a visual medium like film or TV demands that we “show, don’t tell” as often as we can. So, a clever way of revealing a character backstory, for example, is through a montage.

A montage is a series of brief scenes, usually without dialogue, typically illustrating the passage of time. In one of the best Pixar’s movie Up we learn everything we need to know about Carl in this beautiful, memorable montage:

This montage gives the audience everything they need to know about Carl’s marriage. And now that we know we are invested in their love, and can connect deeply to his pain when he loses his wife. We understand why the journey he is about to go on could be exactly what he needs. This was all accomplished through the montage, with no dialogue at all.

You can practice this technique in any screenwriting software, to get a better understanding of how to format this visual exposition. For now let’s use StudioBinder’s free screenwriting software to see what it would look like:

We also see montage used a lot to show a character preparing for a specific event (i.e. “training montage”) or to show a character on a self-destructive binge. While these can be a bit overdone, writing a montage sequence to inform character, or to move your story along can be a very powerful technique, and a fairly simple way to reveal exposition.

Another visual technique to give exposition is the flashback.

Exposition in Film

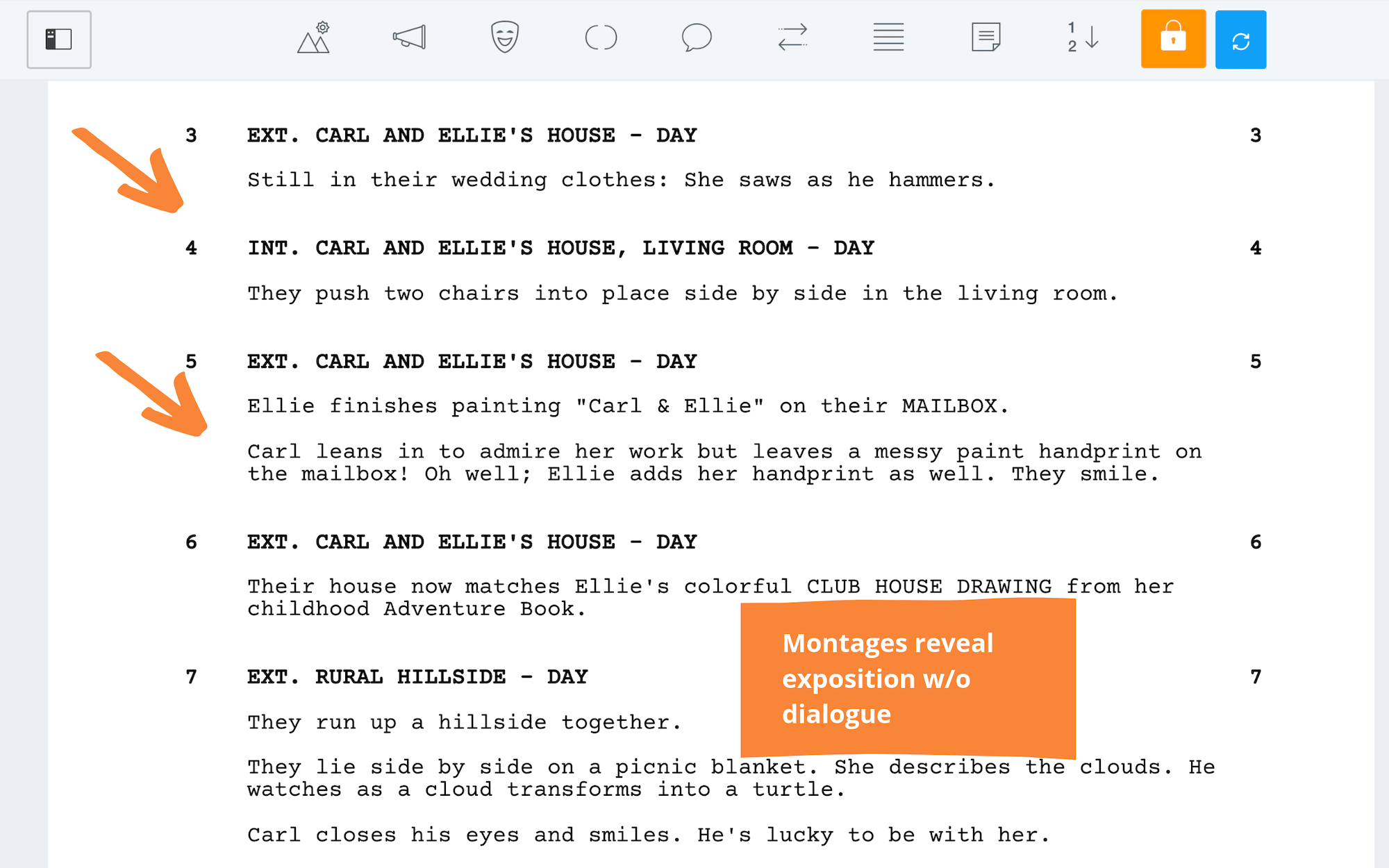

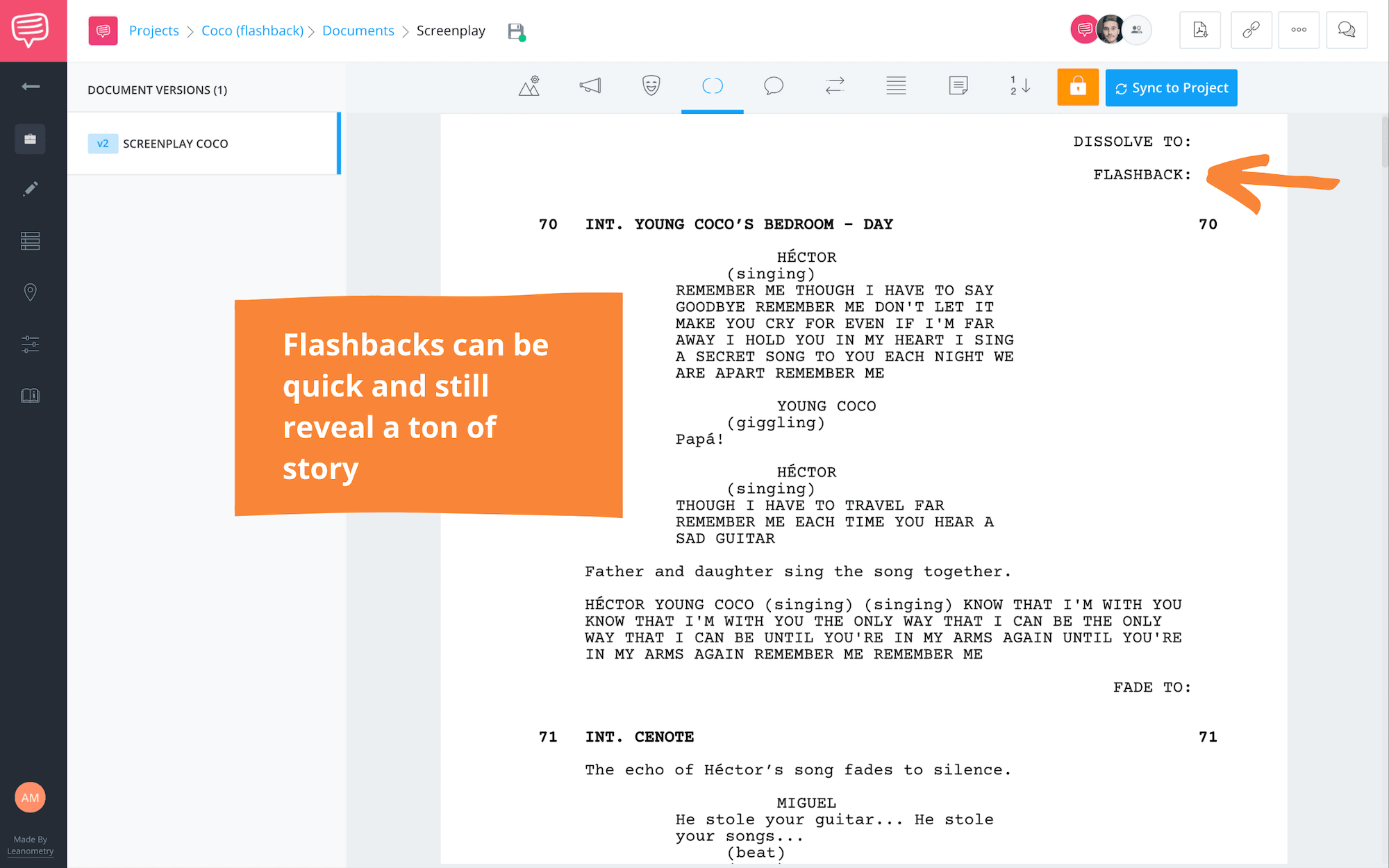

7. Exposition through flashbacks

Similar to the montage is the flashback. A flashback is a scene where we jump to an earlier point in our story, or to a time before the current time.

Like the montage, we can use the flashback to show instead of tell something that happened in the past. What makes a flashback different from the montage is that a montage is strictly a storytelling device.

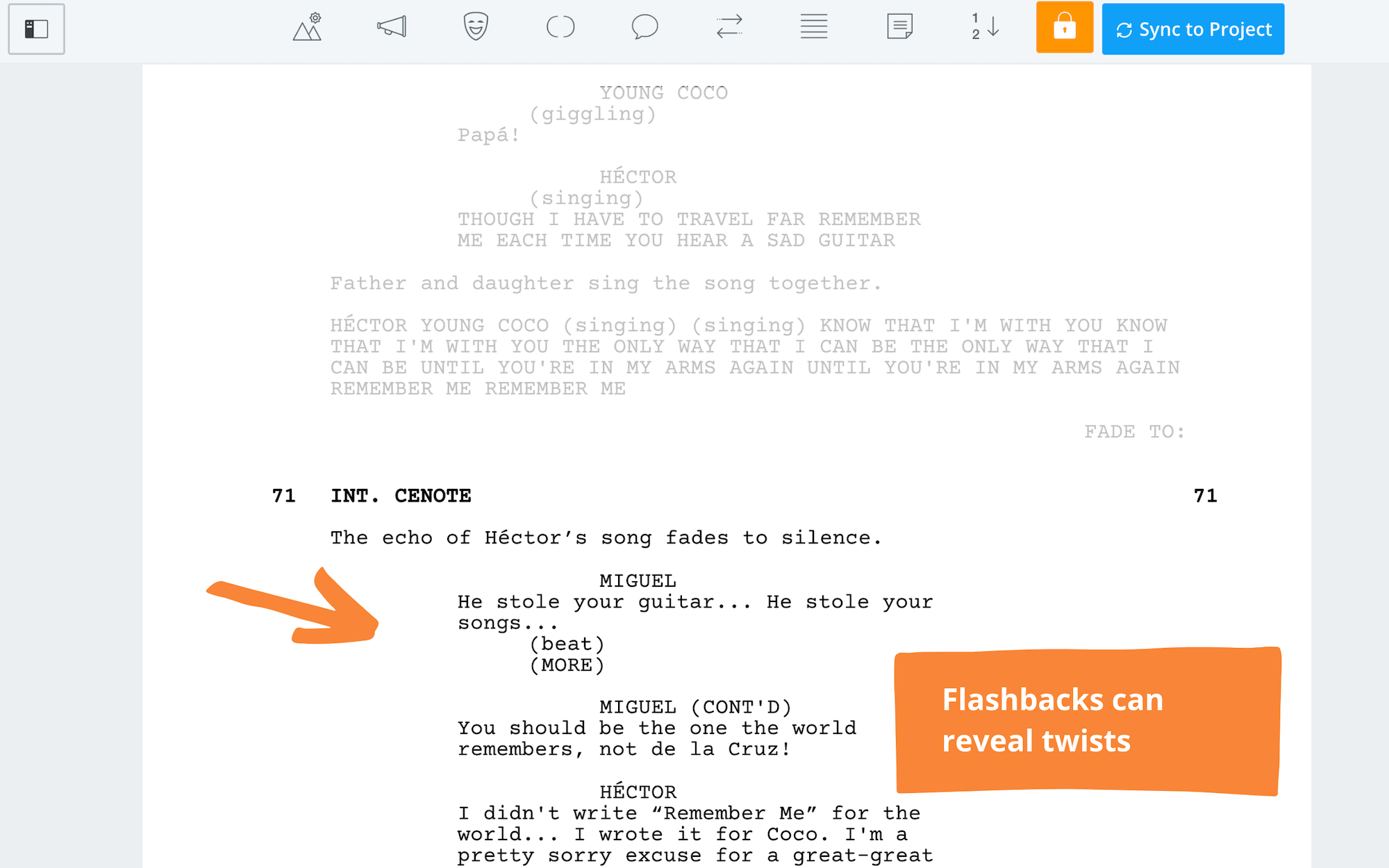

Characters do not “experience” the montage. But a flashback is someone’s past experience, so a flashback must be motivated by character. In Coco, Hector remembers his life:

Like in Coco, flashbacks can be useful to reveal a character’s true intentions, or even information about the setting.

Because of the genre of Coco, being a musical, this flashback was scripted mostly as lyrics. Let’s see how Adrian Molina and Matthew Aldrich revealed this exposition in the writing of the scene:

It's a brief flashback. A quick scene of father and daughter revealing that Hector was actually the writer of the famous song, "Remember Me." We go back to present day, and are met with Miguel's dialogue as he realizes Hector is the rightful songwriter.

But too many flashbacks are confusing and make it hard to follow your current narrative. So once again, make sure it’s motivated and necessary to your character and story. But if done right, writing a flashback is another easy way to reveal information.

Related Posts

Narrating Exposition

8. Exposition through narration

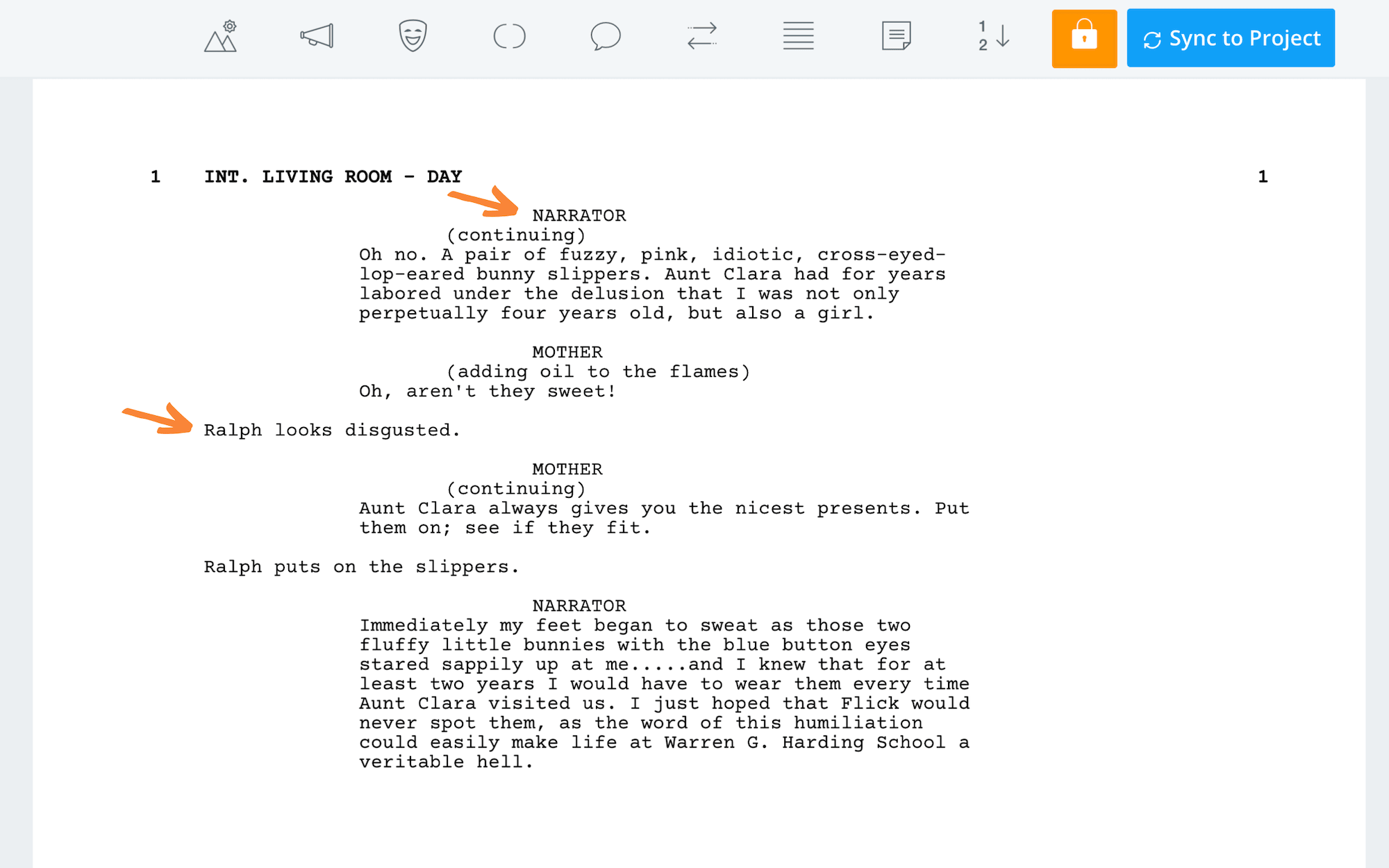

A screenwriting tool that essentially combines the flashback with dialogue is narration. Narration is information provided for the audience’s benefit only. Often it’s told from the point of view of the protagonist recounting the story from some time in the future. So that’s why it can intermingle with the flashback.

Note, even though the flashback is inferred because it’s a retelling, it doesn’t always have to be shown as a flashback. If we look at an iconic scene from A Christmas Story, we have narration of an older Ralphie, but we never see him.

We can use StudioBinder to see how to format narration. It's simple. But in this case, just make sure to distinguish between Narrator, Ralphie, and the younger Ralphie.

…or in this episode from Arrested Development, a character providing secret observations from within the story.

This narration inside of the story is a great way to reveal exposition, especially about what a character is feeling internally.

But narration can quickly become overused. So remember that narration needs to be just as motivated and internally logical as any other aspect of your story.

For example, if you establish that a particular character is the narrator, you can’t really kill her off in the first scene unless you also establish that she’s a ghost relating the story to the audience from “the beyond.”

And of course, there are different styles of narration.

What about those times when characters narrate directly into the camera? This too, can be an effective way to reveal exposition.

MORE EXPOSITION IN FILM

9. Exposition through the fourth wall

We call this style of on-camera narration “breaking the fourth wall”.

We’ve all seen it, it’s not hard to miss. It can have a huge impact on your film, for better or worse. Use it to reveal your critical information.

Fourth Wall DEFINITION

What is the fourth wall?

The fourth wall refers to an imaginary wall that separates the story from the real world. This term comes from the theatre, where the three surrounding walls enclose the stage while an invisible “4th wall” is left out for the sake of the viewer.

The 4th wall is the screen we’re watching. It’s the wall that separates the story world from the real world.

We treat this wall like a one-way mirror. The audience can see and comprehend the story, but the story cannot comprehend the existence of the audience. If you break that wall, you break that accord.

This is called “Breaking The 4th Wall." It can also be described as the story becoming aware of itself.

3 tips for breaking the fourth wall effectively

- Be extreme: This means you need to break the fourth wall all the time, or very rarely.

- Be thoughtful: Consider opportune scenes and moments within the scene for wall breaks.

- Be controversial: Don’t waste your big decision with an underwhelming fourth wall break.

Let’s take a look at an example from the show Fleabag.

This woman is completely detached from her surroundings, so breaking the 4th wall here is brilliant.

In the modern era we tend to see breaking the fourth wall more as a comedic device. But writing little asides to the audience goes back to at least as early as Shakespeare, who used them frequently in his dramas.

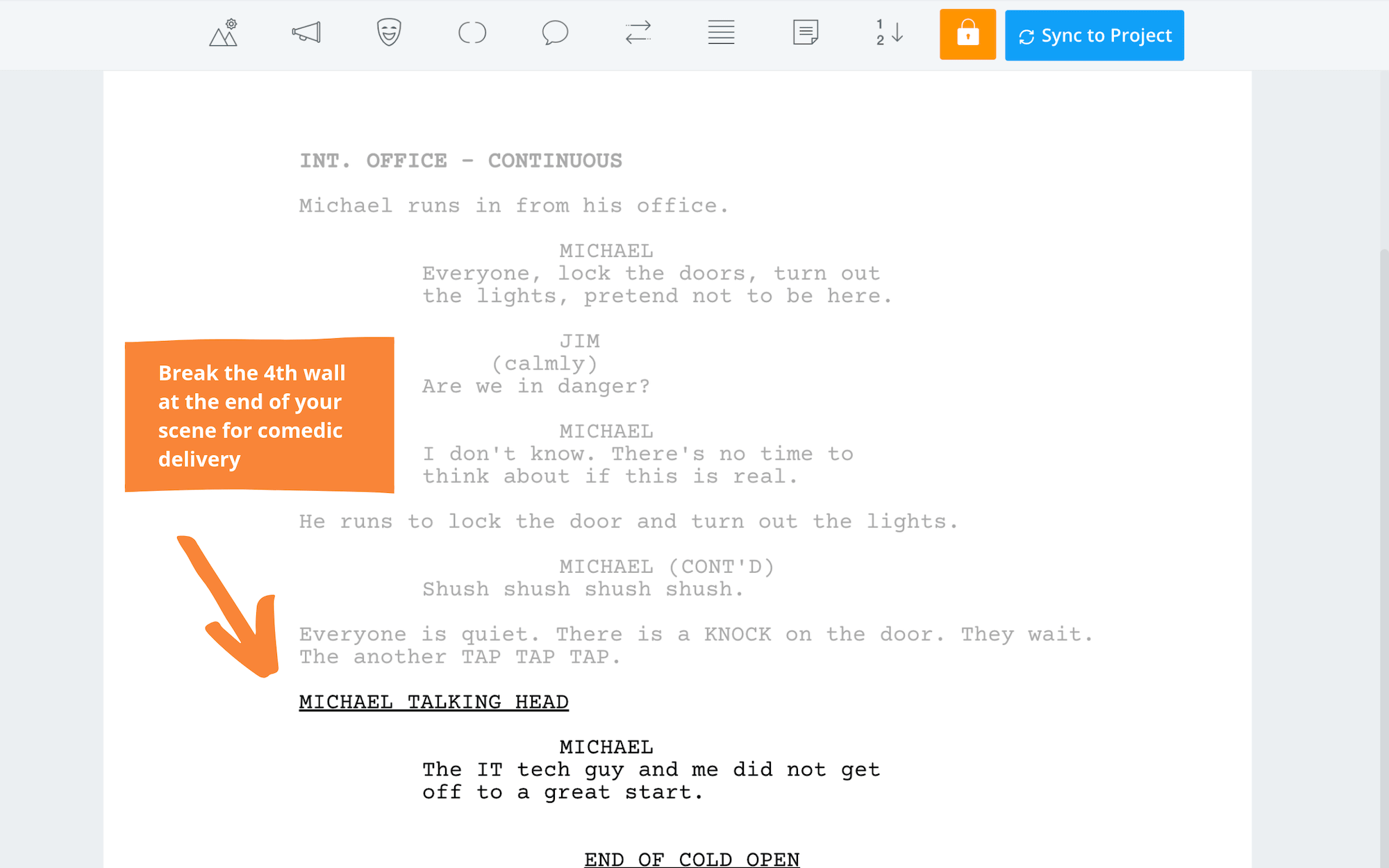

Breaking the fourth wall is another way to reveal exposition. But it doesn’t always have to be by narration. In shows like The Office, or Parks and Recreation, the characters often reveal their feelings by a mere look at the camera. Looking at The Office, we can see how to format.

Many times, breaking the fourth wall is more natural when it comes at the end of a scene if for comedic delivery.

If you want to learn more about this technique, check out this article completely devoted to it.

Related Posts

Post Exposition Examples

10. Exposition through title cards

A sort of visual version of narration are titles. Titles (or “title cards”) have been around as long as the film industry itself.

Modern titles are a very quick and easy way to let the audience know key bits of information without interrupting your story’s flow.

You can use titles anywhere from your prologue to your epilogue. Titles can quickly orient your audience to a location...

Villanelle’s first assassination-Killing Eve

...remind them of crucial plot details that build tension…

HBO’s Chernobyl

… or even introduce characters.

But titles can also be used more creatively. BBC’s Sherlock gives us a wonderful example of how titles (and graphics) can be used to keep exposition from being a stale monologue, as well as give us a bit of insight into the mind of the eponymous character:

Titles can easily become distracting for an audience. Try to use them creatively. Fortunately, current technology allows us to use titles in a lot of ingenious ways.

Texts and Other Media

11. Exposition through diegetic media

A sneaky little way you can get exposition into your story is through media your characters see and/or hear.

Old letters, an emergency broadcast, even text messages are all types of in-story media devices that can clue the audience in to important information. Diegetic sound is sound that can be heard on screen, in the story world. It’s not sound added in later, like narration, or sound effects.

Diegetic media, often expressed as text messages, can be used to establish the main conflict, like in Crazy Rich Asians...

...or to explain how to resolve it like in Shaun of The Dead...

The main thing to be careful of when using diegetic media for exposition is that it can easily be overused, especially in 21st century filmmaking.

While in real life we might only ever speak to certain people via text or social media, it’s not a very interesting thing to sit and watch for 90 minutes or more. But if you do want to pepper it into your film, there are some ways to make texting look better on screen.

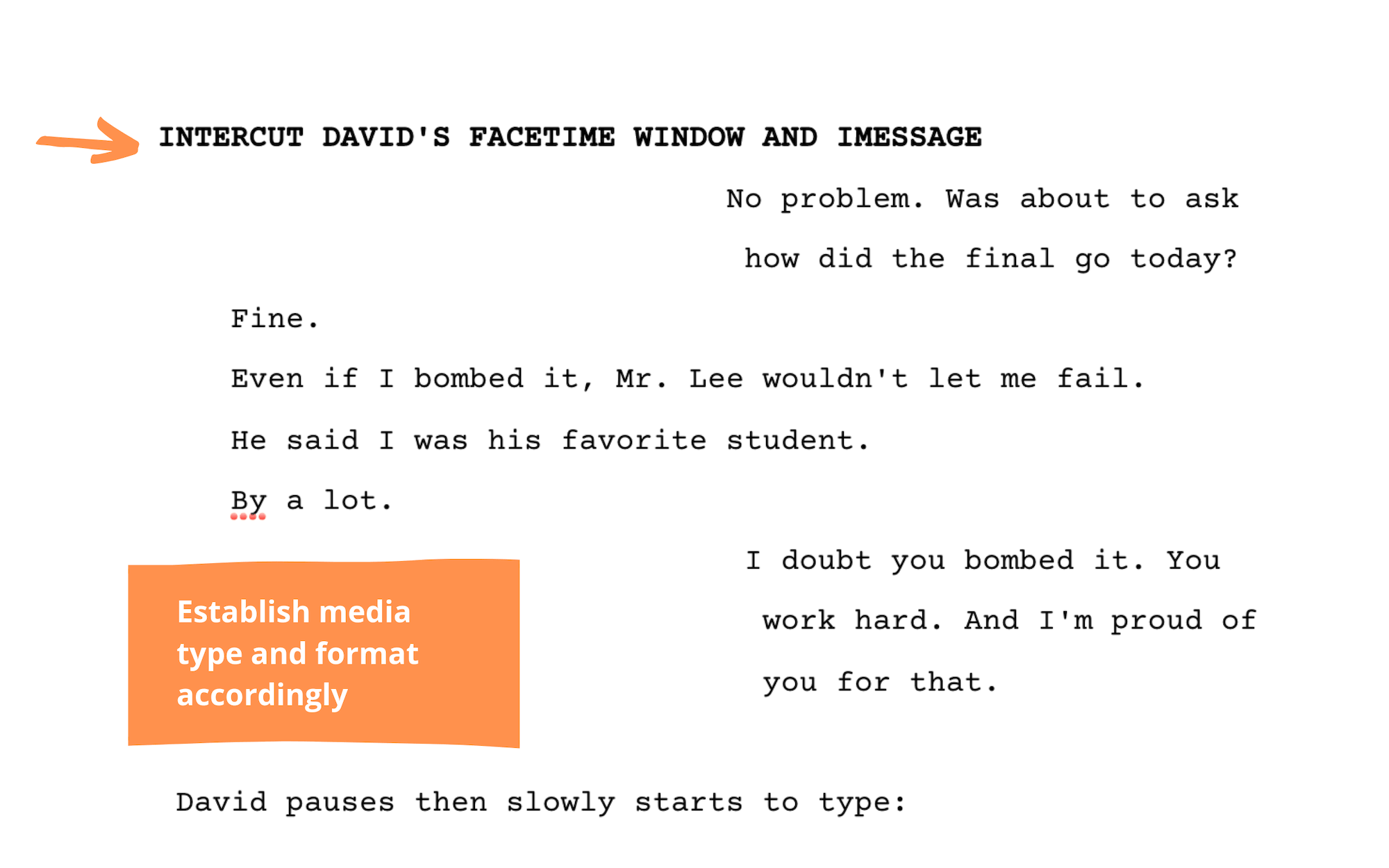

One example is from the emotional thriller, Searching.

Using diegetic media in film

John Cho's character misses multiple FaceTime calls from his daughter. As the day go on, he realizes she's missing. The film shows him trying to find out more about her whereabouts through her computer, search history, and live-streaming services he never knew she had.

So diegetic media was used a TON in this film. Let's check out how they formatted this media in this quick video and then look at a script.

Below is an example from the film. We see a clear heading establishing what kind of media we're going to see on screen. IN this case, it will be an iMessage, so we can format that to match.

Formatting for media can be tricky, and it isn't set in stone. But the biggest takeaway is that it needs to be clear.

Exposition Must Be Organic

12. Exposition should be necessary

Lastly, a point hammered into every section, but that definitely deserves its own– your exposition needs to be organic. It needs to work with the story. It needs to naturally come out of it.

Revealing information to the audience should feel natural. You make this possible by having characters reveal information because that’s their job, like Mr. Keating.

Or you allow the genre itself to take over. A show or film that is fantasy based will likely have a scene or two that requires an explanation, whether through meetings, or some other kind of preparation scene.

If I’m going to write a story about a girl who loses her memory, but slowly starts to get it back, what would be a good way to reveal exposition? Flashbacks might make sense.

If I’m writing a comedy, I might choose to exaggerate some aspect of a character. Say I want to show how overly ambitious they are. That might be delivered best in a montage, rather than narration.

Let the medium match the message.

Exposition is tough. Make it as easy as possible for yourself by trying some of these techniques in StudioBinder’s free screenwriting software.

Related Posts

UP NEXT

22 Pro Tips for Better Dialogue

Now that you have some more confidence in writing your exposition, and even some more techniques on how to execute it organically, let's take it further.

Knowing how to write compelling dialogue can make or break your script. Let's strengthen your skills for you to write your next screenplay.

good job i really enjoyed your actirle